Debunking the Cost Myth: How CANDU Nuclear Delivers Affordable Energy for Canadians

Large nuclear plants is the path to affordable retail electricity rates in eastern Canada.

As much as I love to talk about hydrocarbons, nuclear energy tops the list of my favorite energy topics. I often tell people that next generation nuclear technologies will make hydrocarbons a perennial commodity - an article is forth coming on this exact topic. I wrote an article a couple of months ago that shone a light on an example of what I believe the next natural synergy to develop between nuclear and hydrocarbons, which is in-situ upgrading and refining of unconventional hydrocarbons through electro-resistive heating.

Here in this article, I will introduce Canada’s home grown CANDU reactor technology and will frame it in the light that is most relevant for Canadians and other Western nations today, which is as one of the surest paths to long term national sovereignty and economic productivity.

As shown in the Op-Ed cover image, I wish to juxtapose the concept of energy dependence on the People’s Republic of China (PRC) and its weather dependent power generation technologies or independence through embracing Canadian CANDU power generation.

This is especially true for central and eastern Canada, which are not blessed with natural gas or coal as is western Canada.

While I would love to treat this topic like the pretty huge dork (aka Ph.D.) that I am and mistakenly assume everyone of you loves nuclear chemistry - physics, as much as I do, I will refrain from taking this course in my first dedicated nuclear article. For those of you want a more in-depth look at advanced topics in nuclear physics (e.g., fast breeder reactors, closed fuel cycles), stand-by, this too will become a part of my weekly topic base covered.

Before I introduce Canadian CANDU technology, the first piece of disinformation that I will address is the common claim that nuclear is too expensive and that weather dependent technologies like wind and solar PV are the most affordable because their capital costs are so low.

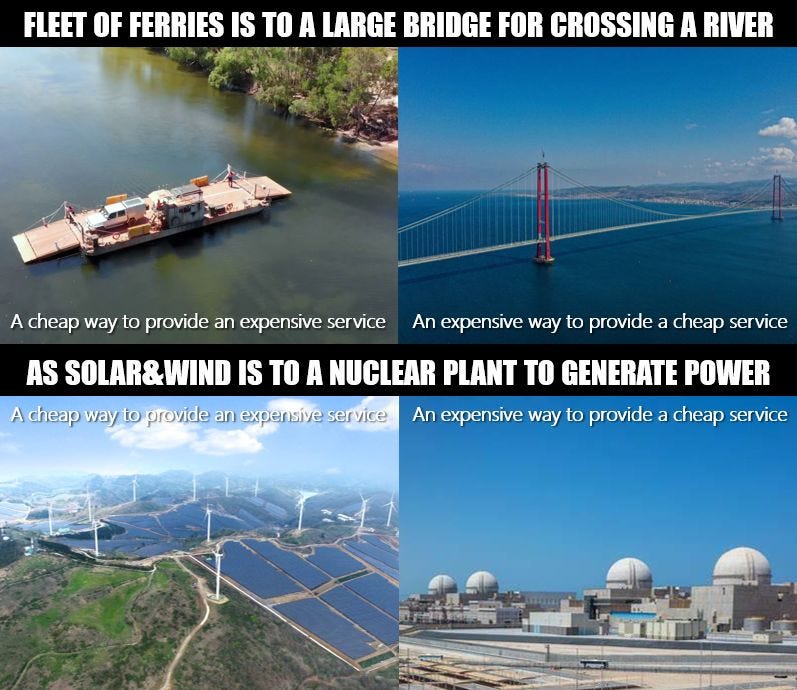

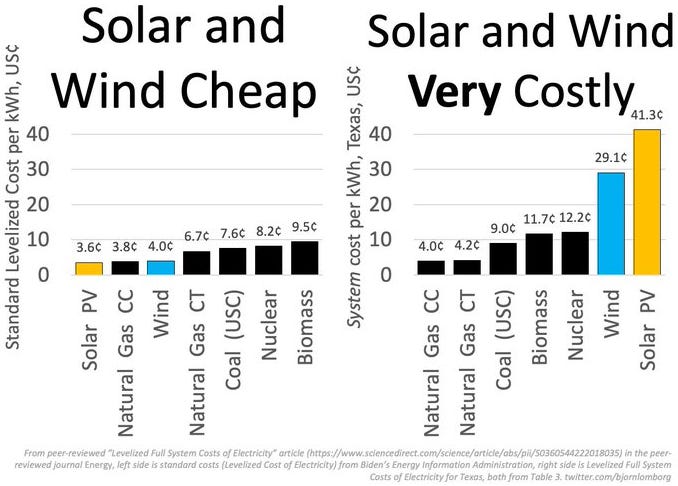

Figure 1a and 1b are two illustrations that I like to throw around on social media when responding to claims by enthusiasts, PR specialists and evangelists of wind and solar PV, who continue to hammer home that large nuclear is simply too expensive.

Figure 1a. Meme that forces people to ask “expensive for whom”.

The large bridge versus a toll based ferry system is analogous to large nuclear power plants (NPP) versus solar PV infrastructure, in that while large bridges or large NPPs are expensive to finance, the utility they provide over the long run is the more affordable option for retail consumers.

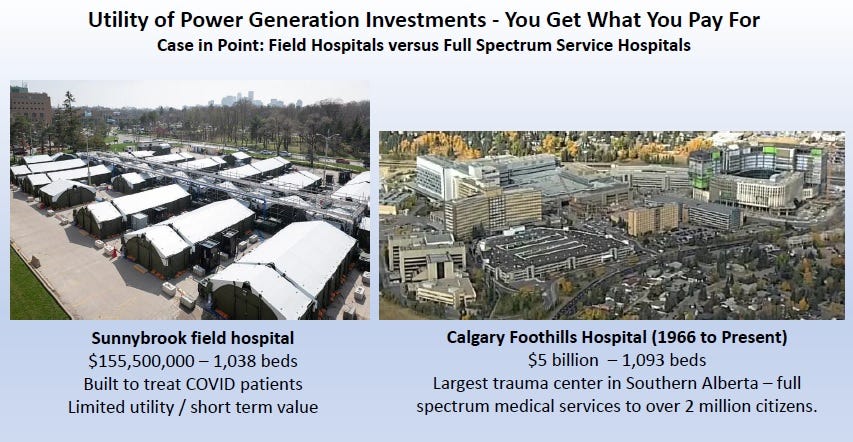

Likewise, the Figure 1b further emphasizes that you get the utility that you pay for. A short-term field hospital has limited long term value, whereas large full spectrum service hospitals provide long lasting utility. Solar PV arrays last at best, a couple of decades and that assumes no hail-storm takes them out, while a large NPP can last upwards of a century with a mid-life upgrade.

Figure 1b. Meme that helps people understand that not all power generation offers the same utility - you get what you pay for.

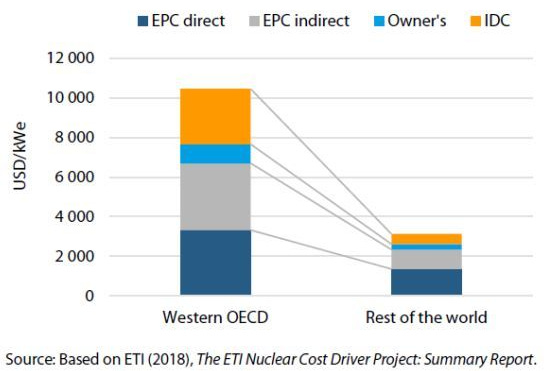

The crux of the nuclear skeptic’s argument is that large NPP require financing north of $10 billion and thus are too expensive. When we consider that 80% of new large NPPs built over the last generation had an average name-plate capacity of 2,500 MW (enough to power 2,500,000 homes), it is true that they require a large up-front investment.

If we use recent specific capital costs (i.e., $ per kW) for large NPPs built in the West (e.g., Figure 2) over the past two decades and multiply by 2,500 MW, it is clear that we are talking about generation infrastructure worth upwards of $25 billion. Even if we use specific capital cost from the rest of the world, we are still talking about $7.5 billion. The massive difference in specific capital cost between the West and the rest of the world is a topic for another day.

Note that EPC means "engineering, procurement, construction” and IDC means “interest during construction”.

Figure 2. Specific capital cost for recent new large nuclear power plants.

The common error or deception used by large NPP skeptics is the argument that such high up-front costs require high retail rates (i.e., $ per kWh). This is an over simplification.

As large NPPs are designed to operate near full throttle and on a 365 / 24 / 7 basis, the actual retail rates required to breakeven are surprisingly low.

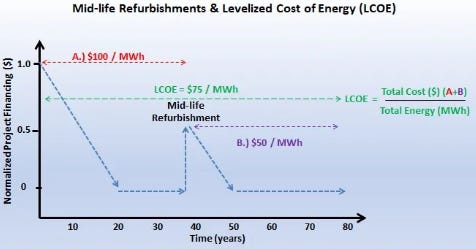

A case in point is shown in Figure 3, which is a meme I produced that was inspired by a recent study done by the Conference Board of Canada with respect to the up-and-coming Phase C 4,000 MW expansion of Ontario’s Bruce Power’s NPP.

The levelized cost of energy (LCOE) calculation that I conducted included the parameters listed and for those not familiar with Capacity Factor (%), it is simply the percent of max power output relative to design capability over the course of a year (8,760 hours). CAPEX is the specific capital cost, OPEX is the specific operating cost and the assumption included 76 years of operation and a mid-life refurbishment that is 50% of the initial total CAPEX.

Note that Canadian CANDU reactors hold the World record for the highest Capacity Factor, as well as the longest uninterrupted operation among most pressurized water reactors (PWR).

As LCOE is analogous to a break-even rate, this exercise shows that over the life-span of the project, a large NPP that uses reactors like the CANDU MONARK, should have no problem in offering competitive rates.

Specifically, as the LCOE in this calculation is $22 per MWh or $0.02 per kWh, an investment banker should be pleased with the perceived financial risks in view of the fact that the average retail rate in Ontario is $0.1 per kWh. In other words, there is significant wiggle room for profitability for an independent power producer even though the up-front capital costs are very high ($20 billion) in this scenario.

Figure 3. Conceptual economics of a large new CANDU MONARK nuclear power plant - Bruce Power Phase C.

Of course, this analysis does not include the massive and unique benefits such a public works investment would bring in the areas of frequency and voltage regulation, as well as medical isotope production. Canada’s CANDU reactors have historically been the largest source of medical grade isotopes (e.g., Cobalt-60) in the World and have saved the lives of countless thousands if not millions.

Key to this rudimentary LCOE analysis is the mid-life refurbishment assumption.

As most of Ontario’s large CANDU fleet is well into their mid-life refurbishment, we are now aware of the impact that this unique feature has on the project economics. Figure 4 shows a simple thought exercise to demonstrate the impact that refurbishment has on the overall LCOE.

Note how the overall LCOE (green) is the average of the initial Phase A (red) and final Phase B (purple) LCOE values and the assumption used is that the refurbishment CAPEX is 50% of the initial total installed cost of the plant. On an inflation-adjusted basis and relative to the initial cost to build Ontario’s Bruce Power and Darlington CANDU NPPs, refurbishment cost 40% to 70% of the Phase A total installed cost to construct (Grok III query).

Figure 4. Conceptual influence of mid-life refurbishment on the overall LCOE of a CANDU nuclear power plant.

If the capacity factor remained the same over both Phase A and B, then the overall LCOE would be $75 per MWh. Most LCOE calculations you see in the literature or on social media do not account for positive impact that the mid-life upgrade has on the life-time LCOE.

Note that refurbishments are only a partial rebuild.

Much of the Phase A civil works last upwards of a century, while power control systems, turbines, generators and reactors are typically upgraded during Phase B. This not only helps with the over-all economics, but it imparts significant environmental benefits (e.g., land and non-renewable material use).

Canadian CANDU reactors are easier to refurbish for reactor core component replacement due to their modular pressure-tube design, which allows targeted, standardized interventions (e.g., replacing 480 tubes vs. an entire pressurized water reactor (PWR) vessel). This design facilitates life extensions to 60+ years without the prohibitive cost of vessel replacement, a rarity in non-CANDU PWRs.

Other Tier I nations (e.g., U.S., France) focus on lighter upgrades or later timelines, with fewer core replacements, making Canada’s CANDU program a global leader in large-scale nuclear refurbishment.

Now that we have covered the positive and typically ignored influence that refurbishment economics have on the LCOE for large CANDU NPPs, I will now introduce the idea of a full system LCOE or levelized full system cost of energy (LFSCOE).

While the LCOE reflects costs from a power producer’s perspective, LFSCOE represents the price paid by the retail consumer, which is typically larger, as the grid is much more than just a bunch of power plants.

The difference between LCOE and LFSCOE has increasingly come to represent the additional infrastructure costs required to stabilize and make available to the retail consumer, the intermittent power produced by wind and solar PV generators.

Traditionally, these additional charges are associated with transmission and distribution (T&D) fees. My August power bill was $157 for the electricity I consumed, but also included $292 for T&D (Combined rate = $0.33 per kWh). Here in Alberta, T&D has exploded over the past decade as the province overbuilt T&D infrastructure to aid the expansion of wind and solar PV assets in southern Alberta - far from load centers concentrated between Edmonton and Calgary.

To illustrate these ideas for different power generation technologies, I introduce Figure 5, which includes estimates from Robert Idel’s recent publication titled Levelized Full System Costs of Electricity, where LFSCOE is introduced to account for full system integration costs, including intermittency and storage for serving an entire electricity market.

In this case, the market used in the Texas ERCOT power market or grid. Note that Robert Idel includes both combined cycle (CC) and combustion turbines (CT) in this analysis, where CT is a simple cycle system.

Figure 5. Levelized Cost of Energy (LCOE) and the full system LCOE (or LFSCOE), where the latter is estimated based on data specific to the Texas grid.

The full order of magnitude difference between the producer (LCOE) and retail (LFSCOE) costs are painfully evident in Figure 5 - as too is it obvious that combined cycle gas turbine (CC) technology provides the most affordable electricity in this jurisdiction.

Therefore, those who argue that nuclear is more expensive than wind or solar PV, are either arguing from a point of naivety or are purposefully disregarding best practice knowledge within the power market (aka disinformation).

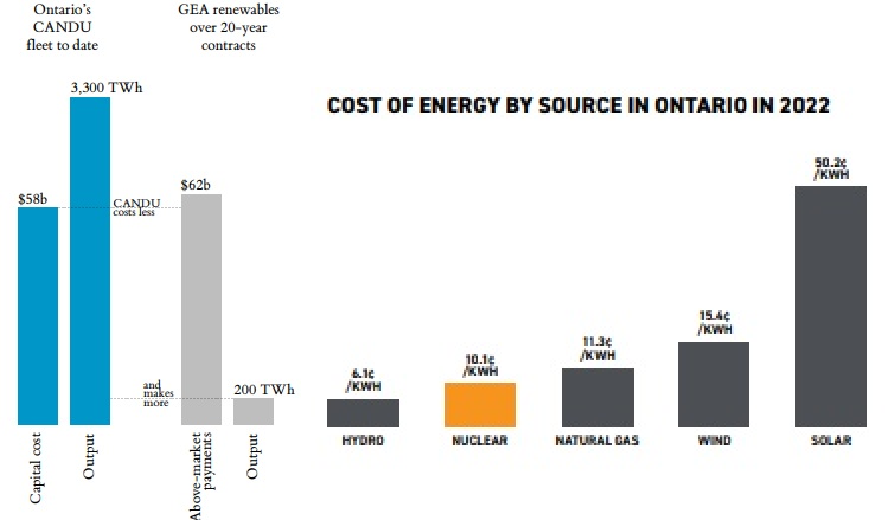

In conclusion, I leave you with data (Figure 6) from the Ontario Energy Board, which confirms my earlier statement that expensive CANDU NPP is the expensive route to producing affordable retail electricity. Note how much more electrical energy is produced from Ontario’s CANDU fleet and its cost to rate payers, relative to wind and solar contracts.

Figure 6. Ontario Energy Board data on rate payer costs (LFSCOE) for CANDU electricity versus other sources.

Now that we have addressed the question of retail affordability for CANDU NPPs, the next article on nuclear will dive into the science and engineering of this national treasure.

Following is an excerpt from a "Clean Technica" substack article:

"Hydro and nuclear are often paired as clean firm power, but they are not equal partners in a renewables heavy grid. Hydro is dispatchable. Reservoirs and turbines can ramp up and down quickly to balance variable wind and solar. Nuclear is inflexible. Reactors are economically and often technically constrained to run at steady output and adjusting them for daily load swings is inefficient and costly. That makes nuclear a poor fit for a grid dominated by wind and solar."

Apparently net zero zealotry makes renewable power generation righteous and everything else sub-righteous. So righteous power generation gets first crack at supplying consumers' needs even though it's intermittent and therefore unreliable. Thus forcing sub-righteous power generation into a peak shaving role to which it may be unsuited. It's like sending a football lineman out on the field to play the position of defensive back or wide receiver - not a winning strategy.

I really hope you and others like you will be able to enlighten the general public such that they see through the arguments of groups like Clean Technica.

A lecture about CANDU in Wellington New Zealand 46 years ago was my first introduction to the inner workings of NPPs. Excellent system.