The James Bay Project - Canada's Hydro Project that Dwarfs China's Three Gorges Dam.

Proof that Net Zero will require large scale terraforming.

Aerial view of the Robert-Bourassa development (La Grande-2), the flood spillway and the reservoir.

Here in this article, I aim to highlight the province of Quebec in Canada, which has approximately 45% of the national hydroelectric capacity (37,500 MW), as a prime example of the scale ecosystem disturbance or terraforming that would be required required in order to rely heavily on pumped hydroelectric storage to enable a Net Zero 2050-like energy transition to weather dependent energy production systems..

Quebec is among the few jurisdictions in the World that has achieved over 95% of its regional power generation from weather dependent technologies. Only Paraguay exceeds the total hydroelectric power generation of the Quebec grid by being virtually 100 % dependent on this form of electricity.

Let me be clear in that I do not view hydroelectric power generation as a net negative for society just because I acknowledge and choose to emphasize the land use intensity of this technology.

This article is intended to serve as a pedagogical exercise.

Likewise note that while I call hydroelectric power generation weather dependent, which is also what I call solar PV and wind power technologies, the former are of much higher utility as they are dispatchable and have a higher availability.

Additionally, hydroelectric facilities often serve to limit seasonal flooding in low-lying downstream communities and collaborate with regional irrigation agencies.

The weather dependence of hydroelectric facilities is seen in the fact that their capacity factor (CF = actual output relative to maximum potential output) is a function of the Seasonal Cycle and to a lesser degree on decadal changes in precipitation patterns.

Here in Alberta, the CF of hydroelectric facilities is tied to streamflow out of the eastern foothills of the Rocky Mountains, which of course is the highest in the spring and the lowest in the winter.

The CF of hydroelectric facilities can vary from a low 10% of maximum in winter to as high as 100% in the spring.

This seasonality in CF is why the annual average North American hydroelectric facility produces 30 to 50% of the maximum rated power output.

This is the clincher folks.

How can a technology such as hydroelectricity achieve 95% of all power generated in Quebec, if common average CF values for this technology varies between 30 to 50%?

The same question applies to wind and solar PV technologies, with their average annual CF values ranging between 10 and 30%.

The answer is large scale storage.

The answer to this riddle for Hydro-Quebec was the James Bay project, which I will show was built with such immense water storage (10x greater storage than China’s Three Gorge dam) capacity that it became the tip of the spear by which Quebec was able to achieve 95% of all power consumed coming from hydro.

Now for a little history.

The roots of Québec’s hydroelectricity lie in the late 19th century, spurred by industrial growth along its rivers. In 1898, the Shawinigan Water and Power Company (SWP) commissioned the Shawinigan-2 plant (Figure 1) on the Saint-Maurice River, producing 5 MW to electrify pulp and aluminum mills near a 42 m falls—the province’s first significant hydro venture.

By 1901, SWP expanded with Shawinigan-3, reaching 194 MW by 1948 through staged turbine additions, its concrete dam replacing early wooden cribs to harness a 1,200 km² watershed. Around the same time, the Montreal Light, Heat and Power Company (MLHP) emerged, building plants like the 1903 Rivière-des-Prairies station (45 MW today).

Figure 1. Turbine installation at Shawinigan-2 generating station in 1911.

A landmark arrived with the Beauharnois Generating Station (Figure 2), begun in 1932 by MLHP on the St. Lawrence River. Initially at 76 MW, it scaled to 1,906 MW by 1961 with 36 turbines and a 24 km canal diverting 40% of the river’s flow—a $130 million project (1930s dollars) powering Montreal. These early facilities, driven by private capital, used Pelton and Francis turbines, transitioning from wood to concrete for durability, and set the stage for larger ambitions as Québec’s population and industries grew.

Figure 2. Quebec Hydro’s Beauharnois run-of-river Generating Station.

The 1944 nationalization of MLHP under Premier Adélard Godbout birthed Hydro-Québec, a public utility tasked with affordable, province-wide electrification. Postwar demand accelerated growth, with Beauharnois expanding via new units in 1952 to its current 1,906 MW, its concrete powerhouse a cornerstone of southern Québec’s grid.

On the Saint-Maurice River, Hydro-Québec inherited SWP assets in 1963, including the La Tuque Generating Station (1940, 294 MW) and Rapide-Blanc Generating Station (1934, 204 MW).

The Ottawa River saw early contributions with the Carillon Generating Station (1964, 752 MW), completed just after this era. Its 14 Kaplan turbines and 62 m gravity dam, spanning the Québec-Ontario border, generate 2,500 GWh yearly, showcasing interprovincial collaboration. By 1959, Québec’s hydro capacity neared 5,000 MW (Canadian Geographic, 2016), or 80% of power, as coal faded and private plants merged into Hydro-Québec’s fold.

Premier Jean Lesage’s 1963 “maîtres chez nous” or “masters in our own house” campaign nationalized all remaining private utilities, cementing Hydro-Québec’s monopoly and igniting a golden age of mega-dams.

The Manic-Outardes Project on the Manicouagan River epitomized this ambition. Manic-2 (Jean-Lesage) (1965, 1,145 MW) kicked off with eight turbines and a 94 m dam, followed by Manic-5 (Daniel-Johnson) (1971, 1,596 MW), expanded to 2,660 MW with Manic-5-PA (1989). Manic-5’s 1,500 m multiple-arch dam—the world’s largest of its kind—impounds a 1,942 km² reservoir, its 12 turbines (plus four at PA) producing 15,000 GWh annually. Manic-3 (1976, 1,326 MW) added six turbines and a 107 m dam, boosting the complex to over 5,000 MW combined.

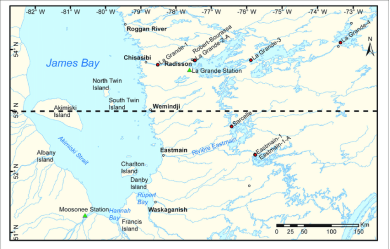

Figure 3. Distribution of reservoirs part of the James Bay Project.

The James Bay Project (Figure 3), launched in 1971 under Premier Robert Bourassa (Figure 4), targeted the La Grande River. Phase I delivered the Robert-Bourassa Generating Station (1981, 5,616 MW)—Québec’s largest—with 16 turbines powerhouse, fed by a 10,000 km² / 80 km3 reservoir.

The La Grande-3 (1984, 2,417 MW, 60 km3) and La Grande-4 (1986, 2,779 MW, 22 km3) followed, each with 12 and 9 turbines, respectively, their concrete dams (110 m and 125 m) harnessing 4,500 m³/s flows. La Grande-2-A (1992, 2,106 MW), an extension to Robert-Bourassa, added eight units, pushing the entire complex past 17,000 MW capacity.

This overall complex represents the largest body of man-made water on the planet, both in terms of surface area (13,000 km2) and storage volume (230 to 250 km3).

These northern giants, enabled by High Voltage Direct Current (HVDC) lines stretching 1,200 km to Montreal, export surplus to the U.S., per Hydro-Québec’s 2025 data. While the James Bay Project is not a single reservoir, but multiple, from the vantage point of its construction history, it’s design philosophy and the 1,200 km HVDC transmission connection to the provincial grid, it serves Quebec’s interest as if it were a single facility.

Most importantly, this ensemble of reservoirs, through its exceptionally large storage volume, functions to stabilize the seasonality of power generation from the rest of the Province’s fleet, and particularly in the winter season when demand peaks while riverine flows are at their annual minimum.

Figure 4. Aerial view of the Robert-Bourassa development (La Grande-2), the flood spillway and the reservoir.

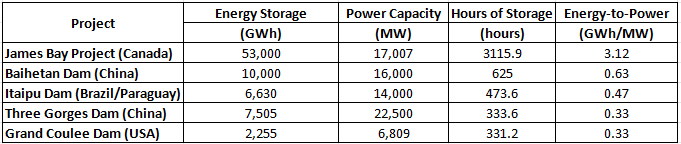

Note from Table 1, the massive hours of storage available at maximum design power for the James Bay Project relative to its global peer hydro-electric facilities. The James Bay Project reservoirs have an estimated maximum storage capacity of 240 km³ and a maximum surface area of 13,000 km², compared to the Three Gorges Dam’s 39 km³ and 1,084 km². This estimate makes use of public data on volume, hydraulic head and an assumed conversion efficiency (90%).

Table 1. Comparison of the energy storage capacity of the James Bay Project relative to its global peer projects.

As shown in Table 1, the James Bay Project dwarfs the energy storage capacity of the World’s largest hydroelectric facilities. Without this immense storage capacity, Quebec would not be able to rely on its hydroelectric capacity to produce over 90% of its electrical energy on a year around basis.

In summary, the overall James Bay project proved to be extremely successful in providing the province of Quebec with the needed storage capacity to make up for the rest of the provincial hydroelectric fleet’s declining CF during the fall and winter, but did so at an immense environmental and social impact.

In addition to the 13,000 km² of Boreal Forest ecosystems that were effectively sterilized, over 2,000 Cree Canadians were forced to relocate from Fort George to Chisasibi in 1981 due to flooding and erosion caused by the James Bay Project’s impact on the La Grande River.

In addition, sediment trapping behind dams starves downstream ecosystems of nutrients, eroding river deltas and floodplains. Water quality degradation—altered temperature and oxygen levels—harms aquatic life, as seen in Quebec’s James Bay Project, where mercury levels in fish rose 400% post-damming, but then gradually subsided to near normal levels today.

In conclusion, these are but some of the examples of the steep environmental and often social, costs that must be paid to create large enough water reservoirs to back-up the intermittency and seasonality of weather dependent power generation technologies.

I argue that the James Bay project serves as an example of the large scale terraforming that would be required in order to rely heavily on pumped hydroelectric storage to enable a Net Zero 2050-like energy transition to weather dependent energy production systems. Canada would require many James Bay equivalent hydroelectric storage facilities to achieve the level of electrification required by Net Zero obligations set forth by the Federal Government.

Fascinating information. As I fondly remember a Doomberg article saying something to the extent that there are no solutions, just trade offs. It must be an engineering masterpiece to generate all that electricity thru all the weather seasons. Enjoyed this a lot.

Fantastic piece! Nice outline of some fascinating history and engineering.

(small error: on Table 1 the Power Capacity should be in MW)

Another great example of a region making good use of their natual resources...and dealing with the consequences, as with all energy projects.